Portfolio

Selected examples of my work from the past several years supporting USAID, Rainforest Alliance, and other endeavors.

From Conflict to Harmony in Tanzania

Inclusive land rights as a catalyst for empowerment and conservation

Produced for Client: USAID

In September 2024, Mary Manyanda Ibiha signed an official certificate recognizing her as the co-owner of several parcels of land in Katoo village in the Rukwa region of Tanzania. Until several months ago, though, it would have been nearly impossible for her to own land or other properties.

Mary’s husband of 33 years, Mlekwa Maganga Machia, is a member of the pastoralist Sukuma tribe, which migrated to Rukwa several decades ago. The Sukuma’s cultural norms dictated that only men could make decisions about land resources and own land, cattle, or other properties. As Mary was the fourth wife—and was unable to bear children—her husband saw no reason to break this tradition.

However, with support from a USAID-funded inclusive resource governance activity called MAST for Inclusive Resource Governance (MIRG), Mary is one of hundreds of women and members of other marginalized groups in Rukwa who have now realized the dream of land ownership for the first time.

“Our husbands used to oppress us. My husband kept insisting that I cannot own land because I’m his fourth wife and cannot bear children. The LEAT team came to help resolve the dispute with my husband.”

~ Mary Manyanda Ibiha

Integrating inclusive land rights and biodiversity conservation

USAID launched the MIRG activity to identify approaches for improving women’s land rights and promoting biodiversity conservation. Implemented by a local Tanzanian NGO called Lawyers’ Environmental Action Team (LEAT) with support from USAID’s Integrated Natural Resource Management (INRM) activity, MIRG has operated in Tanzania since 2023. MIRG launched a pilot program in February 2024 in three villages in the Rukwa region of Tanzania: Kizungu, Katoo, and Nkwilo. These villages extended a broader program called the Resilient Communities Governance Project, which covered 15 villages in Rukwa, offering a helpful means of comparison with the innovative methods used in the pilot to improve gender equality and conservation outcomes.

Pilot results have been promising thus far. In the pilot villages, women participated at an earlier stage, taking part in initial awareness trainings and learning about village land use plans. The percentage of women-owned parcels, secured with documents called Certificates of Customary Rights of Occupancy (CCROs), increased from roughly 37% to over 50%. In comparison, the villages in the broader program had 39% of CCROs registered in the name of women as of September 2024.

In addition, the pilot program reached 255 vulnerable people in the three villages. The team’s understanding of what constitutes “vulnerability” evolved as they interviewed more villagers. Originally focusing on women, youth, and people with disabilities, they eventually came to recognize that a variety of life events can contribute to increased vulnerability. For example, the loss of a spouse through death or divorce can cause major difficulties for women in particular, often leading to homelessness and a total lack of security. Historically, vulnerable people in this region have frequently been excluded from land ownership and leadership roles. Actively including these people in the land use planning process helped to provide security and opportunity that otherwise might not have been possible.

How did the LEAT team achieve these results?

“I’m so thankful I have the CCRO, as it will bring me security. I’m also now an ambassador for other women to encourage them to fight for their rights.

~ Victoria Alex Maliyabwana

An innovative approach to inclusive land use planning

For both the Resilience Communities Governance Project and MIRG, LEAT employed a seven-step collaborative land use planning process (see the Annex for more detail). After meeting with national- and district-level officials, LEAT worked with village members to assess natural resources, map out existing and planned land uses, and resolve disputes. The team used USAID’s MAST approach to identify vulnerable community members and demarcate land parcels.

One of the primary distinctions in this process for MIRG was the introduction of a role called the Social Development Officer, or SDO. The SDO facilitated planning meetings in the villages to increase the participation of women and other marginalized groups.

However, this process was not always easy. For one, many women in the villages were not accustomed to speaking out in community discussions. Many of the men also didn’t value women’s participation in decision-making.

Overcoming these challenges required time, effort, and impeccable listening skills. The SDO and other members of LEAT met with men and women in separate groups.

For the women, LEAT gradually gained their trust and encouraged them to share their perspectives and concerns. By the end, many of the women expressed a newfound confidence and even took on the role of gender champions to encourage other women to stand up for their rights.

For the men, the team spent several weeks building rapport with them and seeking to understand their beliefs and values—before attempting to influence them. Over time, they discovered messages that helped change the men’s perspectives. They highlighted the right to own land for all Tanzanians granted by their Constitution. They also pointed to the risks their families would face if the husbands got sick and were unable to tend to their land or if the husbands should pass away.

For example, with Mary’s husband, a 101-year-old Sukuma man, the team highlighted Mary’s insecurity. If he died, she would be homeless. After 33 years of marriage and raising his children from other wives, he acknowledged that she deserved more than that.

“I’m grateful for the CCRO because, as a disabled person, I’m not given any value. If you’re disabled, your property can be taken by anyone else.”

~ Justina Charles Selemani

Land tenure and inclusion results

Through MIRG, the LEAT team registered 3,054 CCROs in the three pilot villages. These documents grant lifetime rights of occupancy of the land parcel and rights to use its resources.

For villagers like Mary Manyanda Ibiha and other women and marginalized people, CCROs are more than just legal documents—they represent security and opportunity.

At the conclusion of the MIRG pilot in September, this activity had led to:

742 women owning parcels in three villages in the pilot program

255 disabled people and other vulnerable groups owning parcels in the pilot program villages

30 women participating in leadership roles, including village leadership, adjudication councils, or land use councils

51 conflicts resolved, leveraging the satellite maps produced through MAST to provide a clear visual means of identifying conflicting claims to land parcels

Formation of a protected area overlooking two of the pilot villages, which will provide a sustainable source of natural resources and protection against landslides

The inclusion of women and marginalized groups in the land use planning processes has helped to inform the villagers of their rights. It has given them the confidence to participate in the community’s governance and management of their natural resources. Overall, the villagers conveyed a sense of optimism that they would continue to benefit from their land, resolve conflicts more easily, and live in harmony.

“Through this CCRO, my children will live free. They will be beneficiaries of my farm. If anyone tries to grab their land, they will show this CCRO.”

~ Female resident of Nkwilo village

Progress on community-driven conservation

At the outset of MIRG and the Resilient Communities Governance Project, the team conducted a baseline environmental assessment of the area around Lake Rukwa, finding that 20 hectares of land in the area were degraded. The establishment of new farms, unregulated collection of firewood, and grazing cattle had all contributed to the degradation of forests in and near the villages.

To mitigate this degradation, the team worked with villagers to conduct training programs on natural resource management and design land use plans. To make the case with village residents on the importance of protected areas, they pointed out that maintaining an intact forest on the hill above the villages will help to mitigate the risk of landslides. They also described a potential opportunity to obtain benefits through carbon markets, which other villages in the Kigoma region have done.

With the team’s support, the village land use councils developed village bylaws to protect the forests. For example, one bylaw regulates the volume and frequency of firewood collection, levying a 50,000 shilling fine (roughly $18) for those caught taking firewood illegally. Other bylaws include prohibiting free-ranging cattle in protected areas and human activity near water sources.

The community members work together to monitor the protected areas and report offenders. The inclusion of women and marginalized groups in each village has led to increased participation in natural resource management efforts, with more people now interested and involved in protecting their resources.

Lessons learned and further opportunities

The LEAT team shared a range of lessons learned and pointed to several opportunities for further programming:

The importance of the SDO

In independent interviews with LEAT staff members, nearly all of them described the critical role played by the SDO. The SDO proactively seeks to increase engagement with all members of the village, including youth, women, people with disabilities, orphans, and the elderly. Using MAST, the team was able to map out the location of each of these typically marginalized community members and then send someone out to meet with them in their homes or other private settings.

The conversations led by the SDO also helped to uncover some challenges that would not otherwise have been apparent, such as underlying family conflicts that inhibit participation in the land registration process or other village decision-making. The proactive engagement of vulnerable community members in the mapping process also helped to raise awareness and increase participation in natural resource management efforts.

In the pilot, the team introduced the SDO role later in the land use planning process. The team recommends introducing the SDO as early as possible to maximize the equitable participation of all community members.

Spending time to gain trust and build rapport

The LEAT team emphasized the importance of spending enough time upfront building relationships with stakeholders and community members. It’s not enough to simply show up with legal documents and GIS equipment and expect people to get on board. The team first had to connect with regional government officials and then village leaders to gain their trust and support.

From there, they had to get to know the villagers and their ways of life. They sought to understand their culture and how they perceived the world. They connected with them as ordinary people rather than as program implementers. Sometimes, they’d play games like checkers or Bao with them or buy a soda for an elder.

Once the villagers began to see the team as trustworthy, they became more open to joining discussions and hearing the team’s perspectives on land ownership, equity, and conservation.

Joining empathy and technology for conflict resolution

As the team described, “This process is not just about the boundaries of the land, but also the boundaries of the heart.” The messiness of interpersonal relationships was at the heart of many conflicts in the villages. It was essential to make the villagers feel that their perspectives were being heard and taken seriously. While the team originally approached this work from their respective technical fields, they remarked on how they had gained interpersonal skills like empathy and active listening — half-joking that they need skills as marriage counselors.

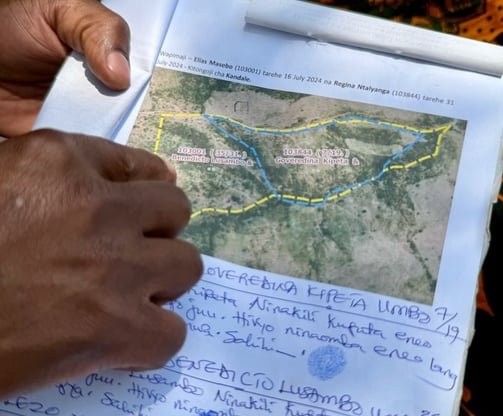

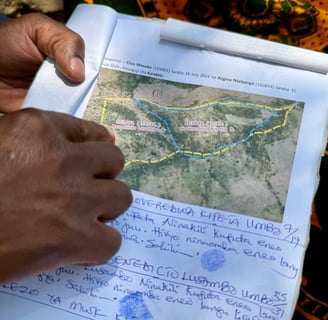

Combined with these “soft skills,” the team found that the satellite images produced through MAST were also essential. MAST provided a clear process to better understand issues causing disputes, identify possible options to resolve those disputes, and support working toward a resolution for conflicts. For example, the overlapping polygons shown in Figure X helped two neighbors understand that they had both made claims to the same plot of land. When they saw the maps, they were able to come to an agreement on the boundaries of their respective parcels.

Impending risk and the need for climate adaptation

Two of the three villages in this pilot program sit on the plateau alongside Lake Rukwa. In spring 2024, intense rainfall caused the lake to expand to the highest level in decades, causing extensive flooding in several villages. Many agricultural plots were swept away, and in one village called Ilanga near the pilot villages, hundreds of homes were destroyed by the flooding. According to the village chairperson of Ilanga, over 350 people had to flee their homes and are now living in temporary shelters on the outskirts of the village.

The LEAT team had recently helped to issue CCROs for many of the settlements in Ilanga destroyed by the flooding, rendering those land certificates now useless to their owners. Many other villages on the plateau face similar risks from extreme weather and lake flooding. Future programming could look at opportunities for climate adaptation for the villages, such as fortifying the protected areas close to the lake and identifying plots more vulnerable to flooding.

A woman in Kizungu had a neighbor who claimed to own the land on her farm. A map generated through MAST showed the overlapping polygons and helped resolve the dispute.

Conclusion

The atmosphere in Nkwilo village was jubilant as the villagers gathered to sign their CCROs on August 30, 2024. For many of them, these documents provide more than just the value of land but also a feeling of being valued as a person. Dozens of women in the village expressed gratitude that because of these official documents, their children will live free and experience security. These women and other marginalized community members described feeling a sense of hope and optimism for the future.

While more work remains to be done, the results in the three villages in the MIRG pilot are promising. The incorporation of the SDO role played an essential role in enhancing the participation of women, youth, orphans, people with disabilities, and other vulnerable community members. The methods employed by the LEAT team could benefit other communities in Rukwa and other areas.

As Respis Augustino Zakaria, one of the parasurveyors trained through this program, described, “Everyone in our community can now access social services. I would like this project to continue with other villages where this work hasn’t been done.”

Women in Nkwilo village celebrate after receiving their CCROs.